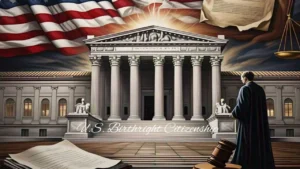

Trump Administration Seeks Supreme Court Intervention on Birthright Citizenship

Trump Administration Seeks Supreme Court Intervention on U.S. Birthright Citizenship. In a move that has ignited significant legal and political debate, the Trump administration has petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to allow the partial enforcement of its controversial executive order limiting birthright citizenship.

The request comes after multiple federal courts issued nationwide injunctions, blocking the order from taking effect.

President Trump signed Executive Order 14160, titled “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship,”on January 20, 2025. The directive seeks to reinterpret the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause, which has historically granted automatic citizenship to nearly all individuals born on U.S. soil. The order aims to restrict this provision by denying automatic citizenship to children born in the United States if their parents are neither U.S. citizens nor lawful permanent residents.

The Evolution and Debate Over Birthright Citizenship in the U.S.

Legal challenges quickly emerged, with federal judges ruling that the executive order contradicts long-standing Supreme Court precedent. A ruling from U.S. District Judge Emmet Sullivan in Washington, D.C., stated that the order “is in direct conflict with over a century of settled constitutional law.”

In response, the Trump administration has asked the Supreme Court to allow partial enforcement of the order while the legal battle unfolds, arguing that birthright citizenship has been misinterpreted for decades. The decision, which the Supreme Court is expected to rule on soon, could have significant implications for immigration policy and constitutional law. Legal experts anticipate a contentious battle as the issue reaches the nation’s highest court, with far-reaching consequences for millions of individuals born on U.S. soil.

What is the History behind the Evolution and Debate Over Birthright Citizenship in the U.S.?

Birthright citizenship, known as jus soli (Latin for “right of the soil”), has long been a defining principle of American identity. Rooted in the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, this doctrine grants citizenship to nearly all individuals born within the country’s borders. However, the interpretation of this constitutional right has been a subject of intense legal and political debate for over a century.

Mark Carney: The New Face of Canada’s Liberal Party and Potential Prime Minister

The Origins of Birthright Citizenship

The principle of birthright citizenship in the U.S. can be traced back to English common law, which held that individuals born within the king’s dominions were automatically considered subjects of the Crown. This idea influenced early American legal thought, but the United States’ racial history complicated its application.

Before the Civil War, the Naturalization Act of 1790 limited U.S. citizenship to “free white persons,” effectively excluding enslaved people, Native Americans, and other non-white individuals. This discriminatory practice was upheld in the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) Supreme Court ruling, which denied African Americans citizenship, even if they were born in the U.S.

It wasn’t until after the Civil War that the legal status of birthright citizenship was firmly established.

The 14th Amendment: A Defining Moment

Ratified in 1868, the 14th Amendment was a direct response to the injustice of the Dred Scott decision. Its Citizenship Clause states:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

This clause ensured that formerly enslaved individuals and their descendants would be recognized as U.S. citizens, fundamentally altering the nation’s legal framework for citizenship.

Trump Backs Amy Coney Barrett as Conservatives Lash Out

Key Legal Rulings on Birthright Citizenship

Over the years, the Supreme Court has ruled in favor of birthright citizenship through landmark cases:

-

United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898): The Court ruled that a child born in the U.S. to non-citizen parents is a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment. This case set a precedent that remains in effect today.

-

Plyler v. Doe (1982): While not directly about citizenship, this ruling reinforced the principle that children of undocumented immigrants have rights under the Constitution, such as access to public education.

The Modern Controversy and Legal Challenges

In recent years, birthright citizenship has become a hot-button issue in U.S. politics, particularly in discussions about immigration. Some political leaders argue that granting citizenship to children of undocumented immigrants creates an incentive for illegal immigration. Opponents counter that any attempt to alter birthright citizenship would require amending the U.S. Constitution, a difficult and highly contested process.

Former President Donald Trump has been at the forefront of efforts to limit birthright citizenship. Most recently, the Trump administration petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to allow partial enforcement of Executive Order 14160, which seeks to restrict automatic citizenship for children born to non-citizen parents. The administration argues that the 14th Amendment has been misinterpreted and should not apply to children born to undocumented immigrants or temporary visa holders.

However, multiple federal courts have blocked the executive order, ruling that it contradicts over a century of legal precedent. The Supreme Court’s upcoming decision on the case could redefine how the U.S. grants citizenship and may have widespread implications for immigration policy.

Looking Ahead: What’s Next?

As the legal battle moves forward, many legal experts argue that only a constitutional amendment could change birthright citizenship, making the administration’s attempt through executive action legally questionable. Opponents of the order claim it could create a new class of stateless individuals, leading to humanitarian and legal complications.

With the Supreme Court set to weigh in, the future of birthright citizenship remains uncertain. The final ruling could not only shape immigration policy for years to come but also set a crucial precedent for the interpretation of the 14th Amendment and executive power in the U.S.

Q&A related to Birthright citizenship:

1. Could the U.S. Supreme Court overturn birthright citizenship?

The Supreme Court has historically upheld birthright citizenship, most notably in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898). However, future challenges could prompt the Court to revisit the issue. While it is difficult to overturn settled precedent, a new legal interpretation of the 14th Amendment could change how citizenship is granted. The possibility of the Supreme Court revisiting this issue depends on ongoing lawsuits and shifts in the court’s ideological makeup.

2. What would happen to children born in the U.S. if birthright citizenship ends?

If birthright citizenship were restricted, millions of children born in the U.S. to non-citizen parents could be left stateless—meaning they might not automatically acquire citizenship in any country. This could create legal complications in areas like education, healthcare, and employment, potentially increasing the number of undocumented individuals in the U.S. over time.

3. Can a president legally end birthright citizenship with an executive order?

Legal experts widely agree that a president cannot unilaterally change birthright citizenship through an executive order. The 14th Amendment explicitly grants citizenship to nearly all individuals born on U.S. soil, and changing this would require a constitutional amendment or a Supreme Court ruling overturning existing legal precedent. Efforts to alter this interpretation have so far been met with legal challenges.

4. How would ending birthright citizenship impact the U.S. economy?

Eliminating birthright citizenship could lead to an increase in undocumented residents, many of whom might struggle to gain legal employment. This could result in a larger underground workforce, potentially affecting tax revenue, labor markets, and access to essential services. Many industries, such as agriculture, construction, and hospitality, rely on workers from immigrant backgrounds, and restricting birthright citizenship could disrupt these sectors.

5. How does U.S. birthright citizenship compare to other countries?

The United States is one of the few developed nations that still grants unrestricted birthright citizenship. Countries like the U.K., Australia, and France have moved away from jus soli, requiring at least one parent to be a citizen or legal resident for a child born on their soil to automatically gain citizenship. However, since birthright citizenship in the U.S. is enshrined in the 14th Amendment, changing it would require a constitutional amendment, which is a difficult and rare process.

6. What happens to children born in the U.S. if birthright citizenship is removed?

If birthright citizenship is restricted, children of non-citizen parents would no longer automatically receive U.S. citizenship. This could lead to a generation of stateless individuals, as they might not qualify for their parents’ nationality either. Without legal citizenship, these children could face significant barriers in accessing education, healthcare, and employment.

Digital Lockdown: Utah’s New Law Forces App Stores to Verify Users’ Ages

7. How would ending birthright citizenship impact immigration policies?

Ending birthright citizenship could have major social and economic consequences. It could make it harder for immigrant families to establish legal status, creating a permanent underclass of people who live in the U.S. but lack citizenship rights. Additionally, enforcing such a change would likely require vast resources, as it could involve tracking and verifying the immigration status of parents at the time of a child’s birth, adding new bureaucratic challenges and legal disputes.

You may also like

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

Leave a Reply